Love as I have loved you: a sermon by The Rev’d Dr Lynn Arnold AO

[Readings: John 13:31-35; Revelation 21:1-6; Acts 11:1-18; Psalm 148]

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of our hearts

be worthy in your sight, O Lord, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

Two verses from our readings this morning have stood

out to me – the first from John’s Gospel:

I give you a new commandment, that you love one another, just as I have loved you, you also should love one another. [John 13:34]

The second from our reading from Revelation:

God will dwell with them, they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them, he will wipe every tear from their eyes. [Revelation 21:3-4]

In hearing those verses this week, in the wake of some encounters in my own personal experience, I have been led to deep reflection upon the meaning of each and to see a deep connection between them – that these verses may be like the beginning and end, the alpha and omega, of divine love. I acknowledge that my reflections have led to some thoughts which can only ever in this life be regarded as speculative about what may await us all in Eternity. But I make these speculations in an attempt to gain some understanding of the possible connectivity between these verses which I have cited.

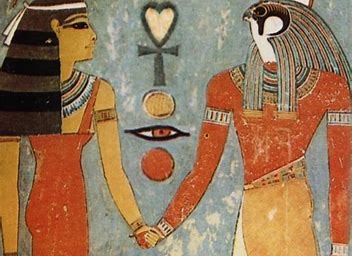

First let me deal with Jesus’ commandment not just to love one another, but to love one another as he has loved us. We’re a sentimental species and Love as a sentiment just suits us to a tee. We’ve been that way from the dawn of time, Egyptian hieroglyphs showing couples holding hands might be oldest surviving record of love etched in stone or wood that we know of, but that might just be because we haven’t yet deciphered earlier billets-doux waiting for us in undiscovered stone tablets or cave walls. Through millenia of loving sentimentality we have also coined love phrases that are designed to make us go doughy eyed; in our own age we have:

Love is like a flower, you’ve got to let it grow

All you need is love, love; love is all you need

And that spectacular piece of faux wisdom from the seventies:

Love means never having to say you’re sorry

With such sentimentality, often seriously in the realm of the saccharine, there is the great risk that we may think we’ve got love taped when we read what Jesus said about loving one another as he has loved us. The problem is that it is too easy for us to overlook that he said these words in the midst of a climactic evening of emotional confusion which had a sense of impending doom for the disciples who had given up everything and cast their lot in with this travelling rabbi. That same evening Jesus had told them that he would be betrayed by one of them and that yet another would deny him; all this against the growing realisation dawning on them that Jesus was knowingly courting disaster at the hands of the authorities. The disciples desperately needed explanation and clarification but he gave them only the utmost in simplicity – love one another as I have loved you.

The explanation and clarification of that simplicity would very soon come in all too shocking ways. Within hours Jesus would be arrested, scourged, unjustly tried and executed. During these travails the disciples would hear very little from Jesus; which is probably why they would remember his seemingly inexplicable words uttered not long before he expired:

Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.

If this was what Jesus meant by love, the disciples must have thought, it came with a horrible price. They could never have thought that loving your enemy as they had heard him say earlier on in his ministry could have meant this. Was this really what he was asking of his followers? How could anyone love in anything like such a way as this?

The answer would come less than seventy-two hours later when the risen Jesus, still bearing the scars of his love for humanity, appeared before the women attending at the tomb and, later, the disciples. This answer was the key to the way Jesus loved to the very end – it was the sacrificial nature of his love. But how is that supposed to look in the way we might love one another, if we are to love others as he has loved us? The reality is that the vast majority of us will never be in a position to be martyrs for Christ and so we can never replicate that extraordinary act of love by such an extraordinary act of sacrifice.

What then remains possible for us? On the front of our pew sheets this morning the Dean, in his message, has noted the recent death of the French-Canadian Jean Vanier whose life and ministry has been an exemplar to all. This is what Vanier wrote about love:

We are not called by God to do extraordinary things, but to do ordinary things with extraordinary love.

So let me now share two examples of ordinary things done with extraordinary love which I have encountered in the past fortnight. The first concerns friends of mine, now in their eighties; a couple deeply in love but who are now being confronted with the fact that the wife is rapidly entering the twilight of dementia and because of this has had to leave their home moving into a nursing home. The husband visits his wife every afternoon for a few hours; during that daily visit they spend time together in the garden, he helping her with dinner and then having a time of particular closeness as they lie down and have a cuddle like two newly weds. An ordinary yet extraordinary act of love.

Secondly, a dear friend and mentor of mine whom I first met when I was appointed to World Vision Australia over twenty ago, passed away this past fortnight. He was in his eighties and is survived by his loving widow who carries a kidney he donated to her nearly thirty years ago; the donation of which must inevitably have shortened his life but had saved hers all that time earlier. An extraordinary act of love.

Pausing for a moment, are you able to recall similar stories of extraordinary love in doing ordinary things? I am certain many such stories will readily come to mind either from your personal experience of the people involved or by report from others. However, the problem is that we may easily overlook their true meaning by being too touched by their surface beauty; and if we make that mistake, we will fail to learn their lessons for the way we are to love.

In our own lives we relate to others in a variety of ways – certainly as a child, possibly as a sibling and a partner and a parent; also in any number of different ways, such as a colleague and friend. Then there are those who are strange to us and yet still, by Christ’s call, a deserved recipient of our love in the way he defined it rather than the way the world would have us have it. How have we loved in such situations?

Let me just give another example from this past week – that of a parent of an adult child who lives elsewhere and who has been confronting a crisis that at times has been overwhelming – a crisis that will have a conclusion but maybe not a resolution. The parent can do nothing tangible to help resolve the crisis and can offer no explanations that can satisfy. The parent can only be there and listen and love – be there at a distance where not even a hug is possible. The parent can only offer love that will bring with it scars of pain felt for the adult child.

Now let me turn to the speculative – a question which, this side of eternity, can only ever be answered by speculation rather than by definition. Will there be the pain of love in eternity? One may assume that love which had never known pain can easily be found there, but what of the love whose deeper roots grew out of and because of pain in this life, where sacrifice or forbearance carried all burdens and griefs before it? We may glibly look to the second verse I cited earlier that talks about God wiping away every tear from our eyes – but might that really mean something much more than some kind of divine, parental kissing it all better? Would such an act of God mean that there will be no remembrance of the pain that caused those tears? But if so, might that also mean there could be no possibility of remembrance of the very love that grew because of that pain?

As we progress through life, we become the person we are due to the very experiences of joy and pain through which we have traversed and the love that we both gave and received along that journey. And that journey we have made will have inflicted upon us scars.

When Jesus rose again and appeared that first Easter Day to the women at the tomb and later to the disciples, he bore the scars that were the price of his ineffable love for the world. He invited Thomas to put his hands in the bloody gashes that his body bore. One might think that to have been a transitory situation and that the scars Jesus bore would ultimately disappear, yet the book of Revelation tells us that it will be the slain lamb that sits upon the throne – the lamb that forever bears the scars of love.

So what of our scars of love? Will we bear those scars that pain in love inflicted upon us during our time in this world when we pass from this life to the next?

There is a theological viewpoint that says that Christians who are persecuted for their faith will gloriously bear the scars of their martyrdom into Eternity. I accept that, but what of the scars that life has inflicted upon us or upon those we love?

Our reading from Revelation tells us that when we present in Eternity at the time of our passing, the tears we may shed from the scars of our loving will be wiped away. Yet those scars will have become part of us, and if they were to be totally removed, we would be less ourselves. My speculation is that God’s wiping the tears will reconcile us to our scars not remove them; just as humanity was reconciled to God through the scars of Christ.

Maybe this is what it really means to be made whole in Christ – that our whole selves, the sum of all our experiences from our journeying through this life will be made complete by the love of Christ – the pain and scars of our having loved included.

Love one another as I have loved you, Jesus said, and if we do God will wipe away the tears of that love but not that love itself.